Rome, Italy

JACOB MORTILLARO HELD THE CRISP PAPER ENVELOPE between his forefinger and thumb, turning it front to back then back to front again, as if deciding whether to slice it open with a pearl-mounted pen knife that dangled from the bright golden links of his watch chain, place it back in the post after scribbling ‘return to sender’ across the front, or toss it into the coal stove.

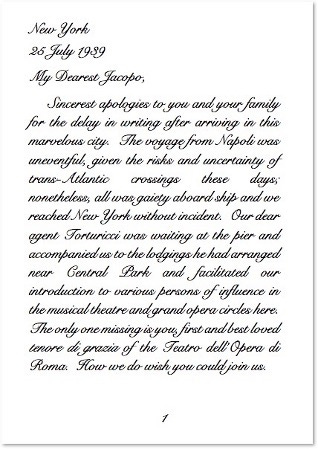

Of course, he would open it. He’d been waiting months for news of Lucrezia.

Jacob refolded the gossamer-thin sheets, returning them to the envelope with its red, white and blue trimmed border and the Statue of Liberty engraved on the cancelled postage stamp that he secreted inside a sheaf of music under a tall pile of leather-bound librettos and books. He thought he could detect Lucrezia’s faint perfume emanating from between the florid lines of her husband’s handwriting. When he thought of Manufredi’s offer of the male lead in Aida, it was the smooth, moist passage between the diva’s thighs that more immediately came to mind.

Working at the Metropolitan Opera would place him close to her again, this time away from the prying eyes of Anna, his wife. It would be a difficult sell but, in the end, she would accept his decision to go. He would frame the proposal as an opportunity to move the family far away from what was shaping up as another exercise in collective madness and the latest chapter in a long history of oppression and abuse of European Jewry.

Anna took the proposal with resolve. They barely survived on his small salary from the Teatro dell’Opera and whatever extra he managed to earn entertaining at weddings and bar mitzvahs, she pointed out. Their increasingly reckless daughter, Atalia, was next to useless. Mussolini had expelled all the Jewish children from the schools after enacting the racial laws only the year before. Now the girl lay about the apartment all day in a deep funk, absentmindedly thumbing her shabby collection of movie magazines and frequenting a nearby cinema after dark, her behavior the subject of many a heated family argument. Little Adamo, practically at his mother’s breast, was too young to contribute anything to the family larder. Finally, they didn’t have sufficient savings to purchase even one third-class steamship ticket to New York, never mind four.

Other than that, Anna informed her determined husband, he was free to go.

THE WHITE SMOKE THAT APPEARED at 17:30 hours on March 2, 1939, had suddenly turned to black. Monsignor Vincenzo Santoro grabbed the telephone and dialed Vatican Radio to reassure Rome, and the entire world, that the smoke was indeed white. Eugenio Pacelli had been elected as the new Supreme Pontiff and the most powerful man in Christendom.

A career diplomat and favorite of Adolph Hitler, the former Papal Nuncio in Berlin, and later Vatican Secretary of State, had negotiated the Reichskondordat of 1933 in which the Church gave moral legitimacy to the Nazi regime at the same time it disenfranchised the German bishops to create a more monolithic ecclesiastical structure with the Pope as supreme dictator. Pacelli now moved himself into the papal quarters along with two caged songbirds and Sister Pasqualina, a Bavarian nun, his so-called housekeeper. Rumors would circulate about the couple, but they were short-lived since by then the world had more distressing matters on its mind. Italy was poised for an invasion of Albania. German troops were amassing on the border with Czechoslovakia. In America, students at Harvard University were swallowing live goldfish.

Then the letter arrived.

In the first week of October, Jacob Mortillaro booked passage on the French steamship St. Nazaire sailing from Genoa to New York via Marseille and Gibraltar using the money that his friend Manufredi had wired him. He caught the morning train at Termini Station in time to put himself on the Genoa waterfront by nightfall. The man would not be seen or heard in Italy, ever again. Nothing further was known of Jacob until the white smoke appeared three times more and his heirs were far from the spot where the Teatro Dell’Opera di Roma’s tenore di grazia had treated the country of his birth and cradle of his singing career to one final encore.

As her husband changed trains at Florence, then Viareggio and La Spezia faded into the distance, Anna Mortillaro gathered whatever family heirlooms she could find and delivered these to the nearest pawnbroker. Over the next months, she would make more visits to this small, bearded man with unruly white hair and tiny oval spectacles hunkered down inside a cubical along the Tevere, a man who’d grown rich in times of adversity, benefitting from the bad life choices made by other residents of the quartiere. Although Shakespeare had lamentably depicted pawnbrokers as being of the Hebrew persuasion, at least during Elizabethan times, this was not at all true in the Rome of 1939. The man’s name wasn’t Shylock. Until recently, many prominent Jews had been enthusiastic members of the Fascist Party and devoted disciples of Il Duce.

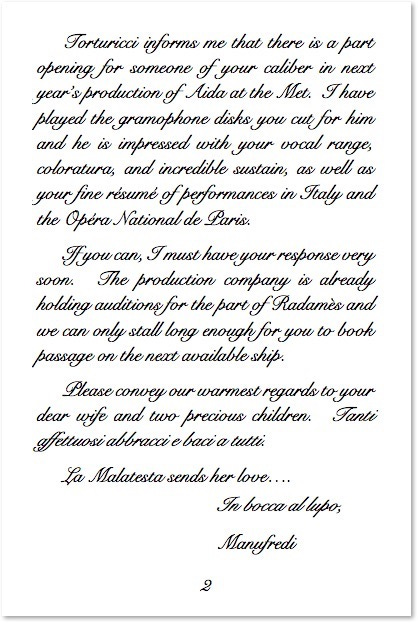

Anna emptied her delicately embroidered, silk handkerchief into a tarnished metal tray laid on the scarred wooden counter in front of her and came away with almost two months’ rent in exchange for her wedding ring, two pearl earrings that had once belonged to her mother, a thin gold necklace with a Star of David pendant, and a slender, white gold lady’s cocktail ring that she’d discovered one day in the pocket of her husband’s overcoat and secreted away without another word. Curiously, Jacob had never mentioned it.

Taking her numbered receipt, she was reminded of the coat check counter at the Teatro dell’Opera and for no apparent reason began to sob. The kindly old man told Anna that she could return there anytime with the repayment and there would not be any interest charged. But don’t take too long, he warned with an uncertain smile.

On the way back to her apartment, she stopped at a news kiosk and purchased that evening’s Il Messaggero, and a copy of L’Osservatore Romano, the Vatican’s own news organ. Later she would peruse the help wanted sections in search of whatever she might chance to find there. Italian industry needed workers for the assembly lines, she reasoned, now that so many young men were being called up for military service and women were taking their places in the factories. Maybe her husband’s leaving would not be so difficult after all.

They’d lately not been getting on well and Anna felt herself approaching that stage of life when physical sex, never mind romantic love, seemed less appealing than sitting down to a good meal and afterwards enjoying a hot soothing bath. She’d long ago sensed that a woman could never experience true love – however the word ‘true’ might be defined – in a man’s embrace and her husband’s departure seemed to prove the point. Only with her children had she felt unqualified affection without any small print in the contract or other extraneous conditions attached. With Jacob, it was always a medium of exchange: he gave her the two children she’d planned for and put bread on the table, she gave him whatever else the man couldn’t provide for himself. There wasn’t a great meeting of minds here, nor any merging of souls. His career in grand opera had not produced the material comforts she’d expected, and the man was often absent from the home for periods of time, sometimes without plausible explanation. All in all, their marriage was a disappointment. Quite suddenly now, and without further ceremony, he was gone.

Despite this jumble of worrisome thoughts, Anna felt herself become unexpectedly lighter as if, in defiance of the odds, she were suddenly free to start over.

AT THE END OF A NARROW COBBLED STREET where she found a run-down little piazza with a badly fractured fountain, Anna placed her copy of L’Osservatore Romano on the mossy marble rim before resting her bottom against the chill stone. A sprinkling of rain had moistened the cover pages of the newspapers that she had held above her head during the walk from the river toward the ghetto and now the limp, inky sheets disintegrated in clumps of papier-mâché in her fingers. Among the center sheets she discovered the advertisements still crisp and dry.

She traced her finger down first the left then the right-hand column of Il Messaggero’s help wanted section then tossed the paper aside and retrieved L’Osservatore Romano. Since she hadn’t any trade or profession, such as nurse or seamstress or hairdresser or pastry chef, and therefore brought no special skills to the job market, her initial search did not look at all promising. The factory jobs were all in Milano or Torino, not Roma, that was, as the Romans themselves joked, a city of “torri, campane, preti e putane…towers, bells, priests and whores.”

Among the unskilled and semi-skilled labor pool, advertisers sought caregivers to attend their aged parents or provide company for an invalid, but this was mainly nighttime work and Anna had her two children to look after. At fourteen, Atalia was as much a burden as four-year-old Adamo. After the racial laws of 1938, all Jewish students were barred from the public schools – which were also Catholic schools since the Lateran Treaty of 1929 gave control of education in Italy to the Church – and her daughter had been forcibly expelled from classes. Since then, the defiant girl came and went as she pleased, even after darkness fell over the city, ignoring her mother’s pleas for caution that sometimes led to angry altercations. Anna didn’t consider Atalia as trustworthy and she could never rely on her daughter to look after her little brother, especially at night when the girl was out roaming the streets, to feed him and keep him safe in her absence.

She thought about taking in laundry or looking after other people’s children but where to start? The Roman nobility and bourgeoisie had live-in nannies and housekeepers. The rest couldn’t afford help.

With no valuables left to pawn and the rent in arrears, the landlord came to collect the money himself rather than sending his daughter as had earlier been the custom. The man was blunt in his proposal. The woman needed something, namely this flat of his that her family had occupied during the past six years. She could pay for the accommodations in lira notes or they could negotiate another means of exchange.

When a husband goes to America, the shameless fellow informed Anna, he finds another woman to fulfill his need. There was no shortage of females, especially in New York. They waited in droves for the handsome Italian men when they disembarked at the wharves in Manhattan, taking their pick and leading them straight home to bed. He knew about these things. He’d been to America himself, worked hard and come back with money to purchase these flats that he rented to people in the ghetto. Now he was enjoying the fruits of his labor. But how many other fine husbands like him had she seen returning from America to their families or sending the passage money as they promised? They rarely ever did.

As he mouthed all these truths and half-truths, his voice became softer and he placed his unshaven face closer to her cheek, whispering. As if they had a mind and will of their own, his fingers began to remove the top button of her blouse, then the next button and the next until he could just slip his rough hand inside to cup one of her small breasts. Anna felt her nipples harden. She knew that a pact had been drawn up and sealed without her having to utter a single word.

WHEN HE REACHED THE GENOA WATERFRONT with the looming St. Nazaire tethered at dockside, a smartly uniformed customs officer examined Jacob’s passport and boarding papers then demanded to see his exit visa.

“All Jews leaving Italy require an exit visa,” he declared.

“Since when is a visa necessary?” Jacob replied, puzzled. “I travel regularly to France and was never asked for such a thing. Is this a new law?”

“Not a law. It’s our policy. You can purchase the visa from me now or stay behind. Your choice. The ship sails at 22:00 hours.”

“And how much is the fee for this exit visa?”

“That depends on what you offer me,” the officer shot back, annoyed by the impertinence of this person whom legislation had now deemed a lesser species. He turned instead to the heavyset, mink clad matron in an absurdly large, feathered hat, cradling a miniature white poodle dog, next in line behind Jacob. He quickly stamped her papers, patted the panting mutt on its moist snout, then handed everything back to the smirking woman who, without a backward glance, strutted boldly up the gangplank into the ship.

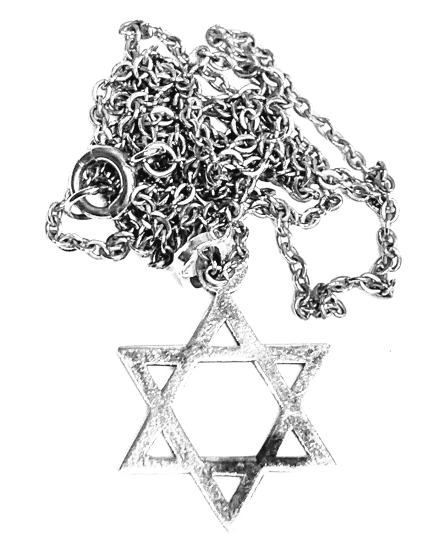

“If you’re not boarding the ship then step aside,” the pompous man in his richly tailored costume ordered. He sported a chrome-tanned leather Sam Brown belt over his considerable paunch in the same way that an overly endowed matron employs a corset, with holstered pistol and brightly colored campaign ribbons dangling from the left breast pocket of his khaki tunic. Jacob wondered whether art mimicked life or was it the other way around? He felt himself at the opera house, under the spotlight again, the love-struck Radamès, captain of the Egyptian guards bursting into song…

The long file of passengers with their battered suitcases and steamer trucks waiting to board, the scruffily clad porters, smartly uniformed ship’s officers and sailors, assorted hangers-on and wharf rats, all broke into hearty applause. The customs goons clapped their gloved hands, shouting, “Bravissimo!” and “Da capo!” Everyone was smiling.

The bemedaled officer reached for Jacob’s documents then quickly stamped them and handed the lot back.

“Complimenti, Maestro, e buon viaggio.”

May 1940

THE LANDLORD FINISHED HIS BUSINESS then reached to the floor to recover his trousers while Anna lay naked on the sweat-soaked mattress that she and Jacob had once shared and where she had birthed her children. She calmly surveyed this unexpected stranger who had so artlessly entered her life, neither lover nor client, and for whom, despite the circumstances and defying all logic, she was beginning to experience a sense of attachment.

The man was coarse and uncultured in practically every way, so unlike the meticulously groomed Jacob with his penchant for learning, extensive knowledge of the Talmud, and his musical abilities. Nevertheless, he was better endowed and more sexually accomplished than her absentee husband and Anna, who despite her timid self was a secret risk taker, had lately decided she would open herself a little to him, that is, she had allowed him to bring her to orgasm which was a feat that Jacob, after so many years, had never accomplished.

After five months without any word, she had come to regard Jacob Mortillaro as her ex-husband and each passing day confirmed the validity of the landlord’s remarks. A man quickly finds another woman to fulfill his need. When a husband goes to America, he rarely comes back. This is what the man had insisted the day he came to collect the back rent and she had no money to pay. The words were pure spezzatura and like a splattering of wine stains they simply refused to wash away.

She had submitted to his advances under duress, in a spirit of acceptance, and without much resistance. The angry, wrathful HaShem was sometimes prone to overlooking acceptance of evil, she thought, if it were done without compromise and out of necessity. Like the virgin daughters of Lot, for instance, who eagerly coupled with their besotted father to prevent the extinction of the whole human race while Sodom burned in the background. Acceptance was one thing, but the Almighty didn’t like compromises. His was a fascist universe starkly delineated in black and white. There were only the victor and the vanquished, which made perfect sense. In a compromise between food and poison, she reasoned, death was the only sure outcome. Therefore, Anna had accepted the inevitable and allowed herself to be vanquished.

Of course, acceptance of a necessary evil could never constitute a good, but then the complexion of things seemed to be changing, at least on her side of the affair. She was acquiring a physical need for this man, like Mussolini had developed an affinity for Hitler despite his keeping a Jewish mistress. Given that she was beginning to receive more satisfaction from their encounters than just rent relief, if she were forced to choose now between the man’s rough embrace and a hot soothing bath, she’d gladly forgo the bath.

He flipped the thick suspender straps one after another over his shoulders, straightened his waistband and patted down the crumpled trouser fronts then, before opening the door to leave, reached into a front pocket to extract a few banknotes and placed them on her dressing table. Anna said nothing, not even thanks. She didn’t need to wash his soiled undergarments or prepare his pasta for him or endure his complaints about her relatives or listen to a never-ending litany of annoyances or share a life that had long since degenerated into a routine of hostility and petty bickering. She wasn’t his wife.

“A deacon of Saint John Lateran owes me some money,” he said to Anna, stalling in the doorway with his crumpled felt hat in hand. “Gambling debts. I can ask a favor, like a job for you cleaning toilets in the rectory or something. Even Jews can do that kind of work. It doesn’t take any skill. Do you want me to talk with him about it?”

“Yes. Please do that for me if you can. You know how difficult it is for us and I need security; that is, besides what happens in this room.” She was careful not to offend this man. He was her lifeline, after all. “I have two children to feed, and I need a steady job.”

“Yeah, sure. Però, mi raccomando…don’t go turning no tricks with them priests, I’m warning you. Sono cattivi, tutti quanti. They’re a bad lot, all of them.”

What began with tenderness had finished in a threat. To him, she was just another whore. Anna pulled the soiled linen sheet tightly over her head and pretended she was dead.

Excerpted from “A Tyranny of God,” an historical fiction novel in search of a publisher.

Brilliant.

The lives of average people in Italy in 1939 are foreshadowing lives of average Americans in the near future.