This is Chapter One in the beta-reader serialization of The Sexualization of Islam, a non-fiction enquiry into how Western ideas of the Orient, and Islam in particular, were shaped by artists’ visions of the erotic and exotic.

Readers’ comments are encouraged but please be respectful.

Access the Prologue to this series here.

BEFORE THE ADVENT OF PHOTOGRAPHY, motion pictures, and Netflix, history was visually recorded in mosaic, painting, and sculpture.

The 18th century scramble for colonization, especially the British conquest of the Indian Subcontinent, followed by 19th century French adventures in North Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific, led to the exploitation of European and American interest in mysterious and exotic cultures. Empire building provided ample material for artists and photographers who pandered to humankind’s noblest, as well as basest, urges.

In the case of Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), critics called his painting entitled “Death of Sardanapalas” a collapse of the distinction between Western culture itself and the “otherness” of Orientalism which, henceforth, provided a safe context in which to place unsavoury or sexually provocative subject matter such as slave trading and harem life, an early form of soft pornography.[1] [2]

“Orientalism” is a sub-genre of “Costumbrismo,” a movement that partook of the realist and Romanticist movements that flourished from the late 18th well into the 20th century. A resurgence of interest amongst contemporary realist artists in recovering the forgotten techniques of Caravaggio and other Old Masters has spurred a revival of interest in Orientalism, especially harem life and the classical “Odalisque,” a word that derives directly from the Orientalist Movement.[3] [4] [5]

The time to invest in Orientalist art is now (always was, always will be). Some works display rather modest price tags while others remain beyond reach of anyone but the uber-rich. The most reliable sources for the intrepid collector are the established art auction houses such as Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Isbilya, Ansorena, Duran, and Bonhams, amongst others. Reputable auction houses can arrange to issue certificates of authenticity sealed by experts in the works of a particular artist, thereby adding value to the piece. The safest approach is to purchase only certified paintings.

Of course, there are always workarounds. If art fakes are your go-to, then hand-painted copies of 18th and 19thcentury exotic and erotic tableau by major artists such as Antonio Fabrés and Jean León Gerome reproduced by contemporary Chinese technicians can be purchased online at very modest prices.

Art copies and fakes, like fast cars and faster women, have never made good investments, as their value tends to depreciate over time. They also wear out, especially when driven too hard.

Perhaps the greatest threat to the fine arts, never mind literature, is Artificial Intelligence (AI) which is already busy rewriting history. AI is poised to flood the consumer market with stunning and relatively inexpensive visual imagery that perfectly matches the drapery and sofa and can be used to wrap the trash when the self-styled art collector tires of looking at a naked woman offered for purchase in an Arabian bazaar by bearded nomads in greasy caftans and sandals.

What is Orientalist Art and why its enduring appeal?

The vast bulk of Orientalist artwork is beautifully composed, masterfully crafted, and worthy of preservation regardless of changing notions of the politically correct. Standing alone in the shining continuum of human patrimony, it offers as accurate a window as we have onto this intriguing and highly controversial chapter in world history.

Art has been defined as a collective impulse to free humankind from its reactive relationship with a hostile world wherein individuals and communities struggle for survival. It is conceptual in nature and practical in its application. Art has documented and celebrated human struggle ever since the first bipeds hunted other animal species while deftly tracing their exploits using natural pigments onto the damp walls of caves. No other species displays this sense of aesthetics, rearranging physical matter in such ways that a third-party viewer is transported away from the long-standing struggle with the elements to a largely imaginary realm of beauty, tranquility, and peace.

Art by its very nature straddles two distinct zones: the social space the viewer occupies versus an idealized, fantastical zone created by the artist. One’s appreciation of any artwork is largely a function of cultural factors and how much information the viewer brings to the experience. In the case of Orientalism, the artist offers information to the viewer that they could not have otherwise acquired, that is, a visit to the Casbah or a guilty peek into the veiled workings of the seraglio, all without the messy inconvenience of conscience or expense of travel.

In the case of Renaissance, Baroque, Mannerist, and Rococo art, whose content is mostly religious or classical mythology themed, even the least educated European viewer enjoys a minimal sense of context. When it comes to Orientalism, however, information circulating about the inner workings of Ottoman, North African, and Middle Eastern harems was largely speculative. Nonetheless, most viewers from Helsinki to Tierra del Fuego instantly recognize and respond to a naked woman when they see one.

Orientalist art catered to a market defined by consumers’ intense curiosity as to what lay beyond their own backyards. It was the product of an era before discount air travel, Airbnb, and adventure tourism, before cosplay, hookup apps, and websites wherein adult role players engage in almost limitless fantasies then return to their staid, mainstream lives as information technologists, bankers, nurses, bricklayers, and national leaders.

Like modern cosplayers, Orientalist artists used their imaginations to create fantastic and aesthetically pleasing worlds while ignoring the misery, pain, and sheer barbarity behind the institutionalized brutalization of women. They imposed a Western template for female beauty and a European sense of opulence on what they perceived as an Oriental backdrop, emphasizing the exotic and erotic while ignoring the actual suffering experienced by participants in that drama, the kidnapped and trafficked women who generally endured harsh treatment and uncomfortable living conditions in their roles as unwilling wives and sex slaves.

In the most fundamental terms, Orientalism’s predominant theme of people trafficking (piracy, abduction, slave trading) and harem life (polygamy and sex slavery) addressed the female urge to be dominated and the male propensity for domination. Regarding the validity of this assertion, readers are urged to navigate to Pornhub, Onlyfans, Fetlife, and other social media platforms with their massive content-creator/subscriber bases and astounding revenue flows. Voila: the digital harem! Better yet, visit San Francisco’s annual Folsom Street Fair which takes place during the last week of September.

Meanwhile, let’s look at a few relatively harmless yet intriguing art pieces to kick-start our journey.

In Fabrés’s “The Thief,” the female subject is condemned for stealing the jewels that dangle from the chain in front of her. The sign overhead states “A Thief ’s Death” in Arabic.

Antonio Fabrés (1854–1938) was a leading Spanish Orientalist painter heavily influenced by the Catalan artist Marià Fortuny. Bolder and more sensualist than the more impressionistic Fortuny, Fabrés endowed his work with jarring images of near-photographic realism. Fabrés seeks to titillate while communicating a potent social message.

Compare Fabré’s “The Thief” to Fortuny’s “A Moroccan”.

Marià Fortuny’s Orientalist depiction of the classic “Odalisque” echoes the theme of Titian’s “Venus of Urbino” and Manet’s “Olympia” exhibited during the same period. Set in an Oriental context, Fortuny’s work dodged the indignant public outcry and disruption by the morals police that Manet’s work elicited in 1863. While Manet’s Olympia is clearly a high-end Parisian prostitute and, therefore, a threat to propriety, Fortuny’s subject is safely locked away in an Arabian harem.

What do the foregoing five paintings have in common? That’s easy. The viewer’s eye is immediately drawn like a beacon to the figure’s right breast.

In Fabrés’ “The Thief” and Fortuny’s “The Moroccan,” the right breast is uncovered, while the more complex arrangements of Fortuny’s “Olympia,” Titian’s “Venus of Urbino,” and Manet’s “Olympia” draw the viewer’s attention back to the same point through a more circuitous route involving a complex structural, and allusion-rich, relationship between the right orb and the subject’s left hand, completing the erotic triangle.

Why the breast and nipple as focal point? The answer is another question: what is a newborn’s first impulse? Check out radio telescopic images of the Milky Way (our galaxy) or McDonalds’ iconic “Golden Arches,” stylized breasts signalling that there’s food here.

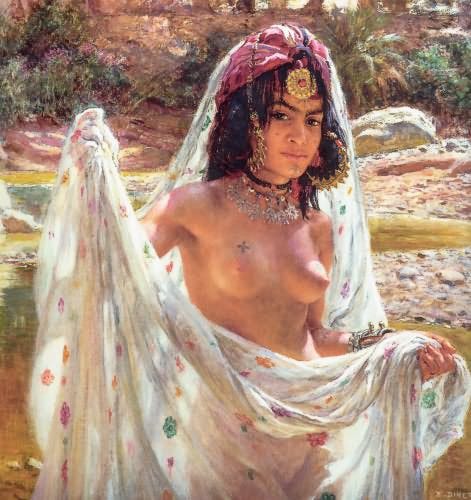

Here’s a gem from my personal collection. Again, the right breast predominates.

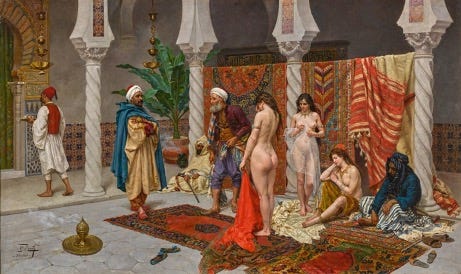

Giulio Rosati’s “Inspection of New Arrivals” (also called “Selection of the Favourite”) was featured in a special exhibition sponsored by the Granada (Spain) Museum of Fine Arts entitled “Odalisques from Ingres to Picasso” in 2021-22. The exhibition took place within the Monumental Complex of the fabled Alhambra, royal palace of the last Muslim kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula which fell to the so-called “Catholic Kings” in 1492.

What is significant about this exhibition is the unheralded backstory.

The fall of the 700-year-old Muslim Kingdom of Granada, of which the Alhambra was its seat of government, coincided with Christopher Columbus’s voyage of discovery to what would eventually become known as the Americas. Columbus’s backers’ (the Catholic Kings Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabel of Castille) intention was not to discover new lands to exploit but to find new trade routes to India and China after the Silk Road had been cut by Muslim expansion and the conquest of Constantinople, henceforth called Istanbul. The discovery of the New World was an unanticipated consequence of what has been mandated by the Quran since the seventh century, that is, the conquest of the entire world and its subjugation to Sharia, what to Western minds at least, represented a return to barbarism.

The location of the exhibition is significant in that it is thought by critics to be the actual setting for Rosati’s iconic painting “Inspection of New Arrivals.” By Rosati’s time, however, the Alhambra fortress and Generalife (living quarters of the ruling family) were in ruins, their formerly magnificent chambers inhabited by an eclectic collection of gypsies and rough-living street folk whose oral literature provided the American writer Washington Irving (1783-1859) with material for his enticing collection of short stories entitled “Tales of the Alhambra.”[6]

Orientalist painters needed to be experts, or at least intimately familiar, with the trappings of their genre: the architecture, costuming, and especially fabric designs, tapestry, and the coded-pattern carpets displayed in practically every tableau. Like the historical fiction writer and novelist, the Orientalist painter conjured vignettes pregnant with backstory involving the kidnapping of white slaves and their selling into the vast, lucrative markets of North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, and throughout the Middle East. Not only did they need to keep up with current events – white slavery was a hot issue from the early 17th to late 19th centuries and lingered well into the 20th – but they were skilled antiquarians versed in the native arts and aesthetics of Egyptian, Arab-Muslim, and Ottoman society.

Rosati’s “Inspection of New Arrivals” is an excellent example of the level of expertise displayed by the finest Orientalist artists of the era. Rosati trained at the Accademia di San Lucca in Rome and later under the tutelage of Spanish history and genre painter Luis Alvarez Catalá, himself having been a student of the famed Orientalist painter Marià Fortuny. All were detail-oriented aficionados of Arab life generally and harem life in particular, to the extent of what could be known by outsiders.

From Sotheby’s catalog description of Rosati’s painting on the auction block:

“Hanging between the columns, from left to right, can be seen an Oushak 'Medallion' carpet, West Anatolia, 16th/17th century; a Kirshehir prayer rug, Central Anatolia; and a North African/Berber rug. The two figures on the right sit on a Southwest Caucasian, possibly Gendje, carpet; in the right foreground is a Mudjur prayer rug, Central Anatolia; while the three central figures stand on an Oushak 'double-niche' small medallion rug, with cloudband border.[7]

Some Orientalist artists spent years in North Africa and the Middle East. Alphonse-Étienne Dinet (AKA Nasraddine Dinet) (1861-1929) was a Frenchman who took up residence in Algiers and eventually converted to Islam. Dinet's understanding of Arab culture and his proficiency in language allowed him to find nude models in rural Algeria where the burka, niquab, and hijab were less frequently imposed.

Josep Tapiró Baró (1836-1913) was a friend of, and fellow student with, Marià Fortuny at the Escola de la Llotja and later in Rome. In 1871, he and Fortuny embarked on a journey to Tangier where Tapiró was bitten by the Orientalist bug. Tapiró left Rome following Fortuny’s early death in 1874, then joined a Spanish diplomatic mission to meet with Sultan Hassan I in 1876. He moved into a newly built house near the medina quarter of Tangier and acquired an old theater which he adapted into an art studio. In 1886, he married twenty-year-old Maria Manuela Valerega Cano, a Tangier native of Italian ancestry and remained in Tangier for the remainder of his life.

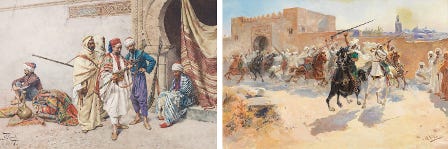

English watercolourist and engraver Charles Robertson (1844-91) first travelled to North Africa in 1862, following in the footsteps of many other young artists mesmerized by the mystique of the East after the French conquest of Algeria in the 1830s. He travelled throughout Algeria, Morocco, Egypt, Jerusalem, Damascus, and Turkey. Note Robertson’s dramatic use of perspective and his attention to detail in the rugs and tapestries displayed for sale. Also note that there are no women depicted in the scene, a man’s world.

Antonio Fabrés and other 19th century artists produced stunning portraits of both women and men in Oriental dress, as well as landscapes and scenes of family and village life.

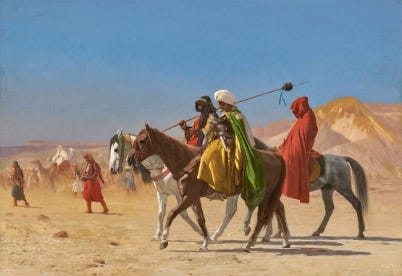

Despite cities and villages that resembled rabbit warrens teeming with poverty, disease, crime and political intrigue, life for most North Africans remained unsettled and nomadic before the discovery of oil deposits in the Arabian Peninsula.

While not all Orientalist art is about naked women sold in the slave markets or groomed for sex in a harem, one cannot escape the sensuality imbued in the work. The sublimation of sex has always been expressed in men’s attraction to arms. By exercise of their physical prowess and skills with weaponry, men take women captive in wars and slave raids, raping and pillaging along the way. The nomadic life, which by nature precludes agriculture, or even animal husbandry, trends toward banditry, while slave trading is humankind’s most ancient commercial activity.

The homoerotic elements in Jean-Léon Gerôme’s “The Snake Charmer” assign a role to prepubescent boys in the Islamic pantheon of sexual proclivities, although the hadiths prescribe death to anyone caught in flagrante delicto with a same sex partner. Perhaps these images say more about the painter and the tastes of his audience than the actual subject matter. More on this later in the series (Chapter Four - Boys in the Harem).

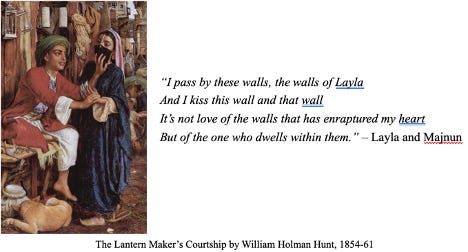

Not only was homoeroticism coded into these paintings, but the Western concept of romantic love, like that of feminine beauty, was also imposed on the oriental template. Nonetheless, one somehow gets the idea that the wooed woman, who may end up as wife number four, is hardly an equal partner.

Since this treatise is about the sexualization of Islam as depicted by Western artists, we won’t dwell too much on scenes of daily life in Istanbul, Cairo, the Arabian Peninsula, Damascus, or any city, and especially not modern-day Dubai.

A city planner who worked as a Western consultant in Dubai described to me how Western architects steadfastly refuse to enter some of the fabulous skyscrapers and other monuments to wealth that they had designed for their petrodollar-rich clients. Substandard workmanship in the service of unreasonable and often unachievable demands for fantabulous designs, exacerbated by compressed schedules, have led to predictions of imminent collapse. This was also his prediction for Arab society after the oil deposits run out. Orientalist artists’ depictions of desert life may again become current reality, at least for those without assets squirreled away in the United Kingdom or elsewhere abroad, making Orientalism the most prescient and enduring movement in art history.

Those who cannot afford to invest in art, but nonetheless yearn for the Orientalist experience, can fly into the Spanish city of Seville where they are invited to dip a toe into the original, repurposed Arab baths (the “Eros” experience is priced at 445 euros per couple) then grab a bus to Tarifa for the 32-kilometre ferry crossing of the Strait of Gibraltar to Africa. The old city and bazaar of Tangier are as they always have been and, like Seville’s Arab baths, are tourist friendly. Bring lots of cash. There may even be some sex slaves for sale, or at least for rent.

Next: Chapter Two - The Slave Market

Footnotes

[1] Nochlin, Linda (1989). "The Imaginary Orient". The politics of vision: essays on nineteenth-century art and society. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 42–43.

[2] Artble, The Death of Sardanapalus. https://www.artble.com/artists/eugene_delacroix/paintings/the_death_of_sardanapalus

[3] Nancy Demerdash, The Origins of Orientalism, Orientalism-Khanacademy-Google Classroom. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/introduction-becoming-modern/issues-in-19th-century-art/a/orientalism

[4] Maya Jiménez, Costumbrismo, Khanacademy-Google Classroom. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-americas/latin-america-after-independence/art-of-mexico-in-the-18th-and-19th-centuries/a/costumbrismo

[5] Wikipedia, article, Romanticism. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romanticism

[6] A pioneer in the art of travel writing, Washington Irving’s stay in Spain resulted in publication of “A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus” (1828) that saw 175 editions before the end of the century. “Chronicle of the Conquest of Granada” followed in 1829, then “Tales of the Alhambra” in 1832. See: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/403733.Tales_of_the_Alhambra

[7] Sotheby’s, auction results for December 11, 2023, 19thcentury European paintings, Lot 9.https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2019/19th-century-european-paintings-2/giulio-rosati-the-favourite

There's history.

And then there's the history behind the history.

This article takes us to what has really driven us in so many ways.

Medium has a feature where we readers can highlight particular words, sentences, and paragraphs. I use this feature for literary devices that have caused me to think differently. I would used that feature on this Substack article.